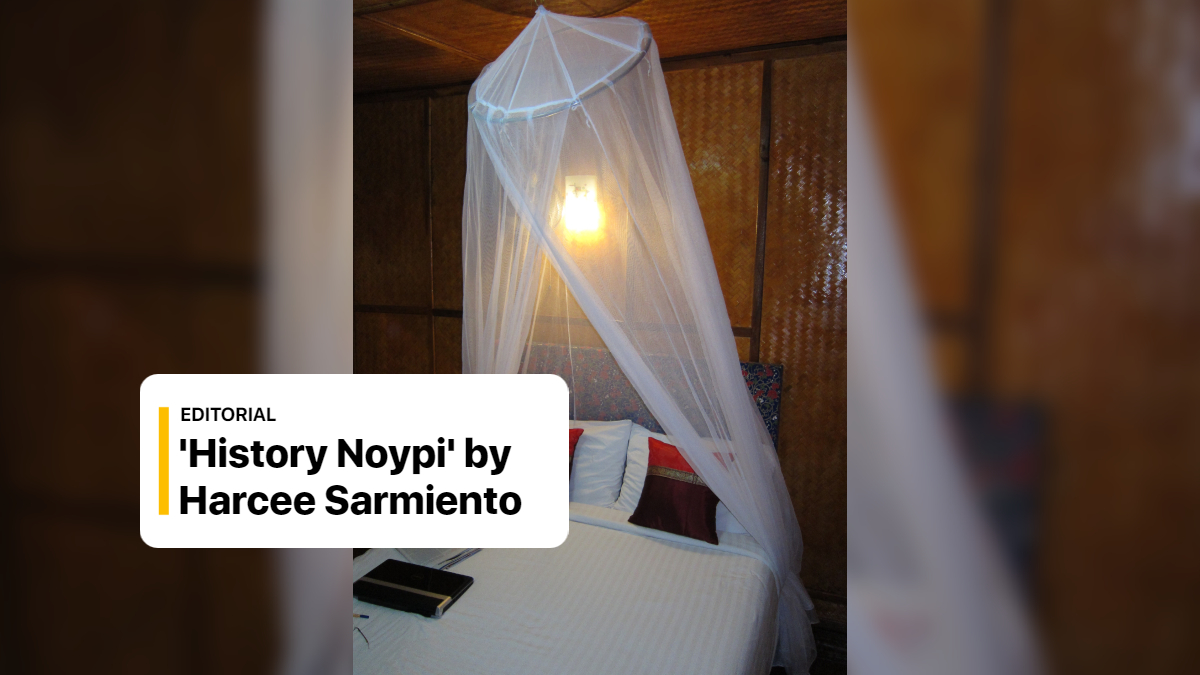

If we are about to make a list of things that make us Filipino, kulambo or mosquito net will make it on the top 10. Up to this day, this modest sleeping necessity stood its ground in protecting Filipino families against dengue and malaria, despite the presence of many alternatives.

Unbeknownst to many, the kulambo that we know for its humility and straightforwardness was a luxury back in colonial times. With the rampant cases of malaria back then, kulambo has become the primary defense against mosquito bites – well, for those who can afford it.

An article published by La Verdad with the headline No Mas Mosquitos (No More Mosquitos), issued January 21, 1903, page 6, cited that some Filipinos were “content” in using kulambo to “save themselves from mosquito bites”. The article called it a good method, however limited only “to those with fortunes” and the poor like the peasants must endure the stings of these “unsanitary vaccinators”.

The article also cited that even some can-afford Filipinos hate the kulambo because it’s uncomfortable in the hot weather. How about those who can’t afford it? La Verdad’s article suggested natural anti-repellants which include hanging of lavender branches, eucalyptus plant, and tangan-tangan (tawa-tawa?) or castor bean plants.

In 1900, Philippine Tropical Disease Board Members made up of American soldiers and health officials, arrived in the country and saw how critical the health situation of the Filipinos was. The death rate was 81% among Filipinos, while 72% among Chinese in the country. Lieutenant William J. Calvert associated the high death rate with “poverty, poor food and dwellings and ignorance” of the Pinoys.

The Americans were very serious in dealing with these epidemics. In a study by Gibbons et.al, (2012), dengue has been the major illness among US servicemen in the Asia and South Pacific region.

And of course, the availability of the technology then wasn’t enough to combat epidemics like malaria and dengue. Experts were just starting to gain knowledge of it. To suffice the lack thereof, American officials ordered people, especially children to sleep under the mosquito nets. It was a simple, but very effective solution, indeed; even today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests its usage.

According to history, mosquito nets are as old as ancient times. Egyptians are believed to be the first to use them in their beds, called conopium (cōnōpē^um). These were used to protect them against gnats and other insects. Probably, when Moses asked the heavens to retaliate on Israel’s behalf, Egyptians battled God with kulambo when the plagues of gnats (lice) stroked them!

In the Philippines, the kulambo has a fair share of the romantic culture that we have. In a traditional Magindanaon wedding, before sunset, the bride and the groom go to the groom’s house. Both of them will change their attire, share festive foods with the entourage, and will receive gifts. Afterward, they will go straight to the bride’s house where the bed is set for them, including the “ulul” or “mosquito net”.

Assisted by the relatives, who are watching them, the two will be laid inside the mosquito net. In other practices they call “kapedsugay”, the groom teases the bride with a kiss inside the kulambo. The bride will try to “escape”. When he gets to her, that’s the end of the show and the start of the “honeymoon”. Of course, the show ends when the bride is caught!

Today, the humble kulambo remains the Filipino premiere weapon against mosquito bites. Despite technological advancements like air-conditioning and mosquito repellants, it is still thriving in many parts of the country. The community in Ibaan, Batangas takes pride in their woven mosquito nets. At one time, the community supplied 90% of the kulambo in the country, earning its title as the “Kulambo Capital of the Philippines.

In El Nido, Palawan, they put the kulambo in another level of admiration. As luxurious as the place is, the Palawenos honor the lowly kulambo with a three-day celebration they call the Kulambo Festival. Townfolks dance, sing, and parade dressed in colorful kulambo, to show the role it plays in the town’s effort to eradicate malaria.

Speaking of “showing off”, who can forget how the Duterte administration used kulambo to show how simple is the life of the former president? Whether it was for propaganda or not, it was a very smart move since numerous Filipino households relate and continue to snuggle under a mighty kulambo to give them a restful and safe night even to this day.

No one knows how long the kulambo will stand the test of time. But one thing is for sure, it will remain a Filipino symbol of resilience, ingenuity, and humility.