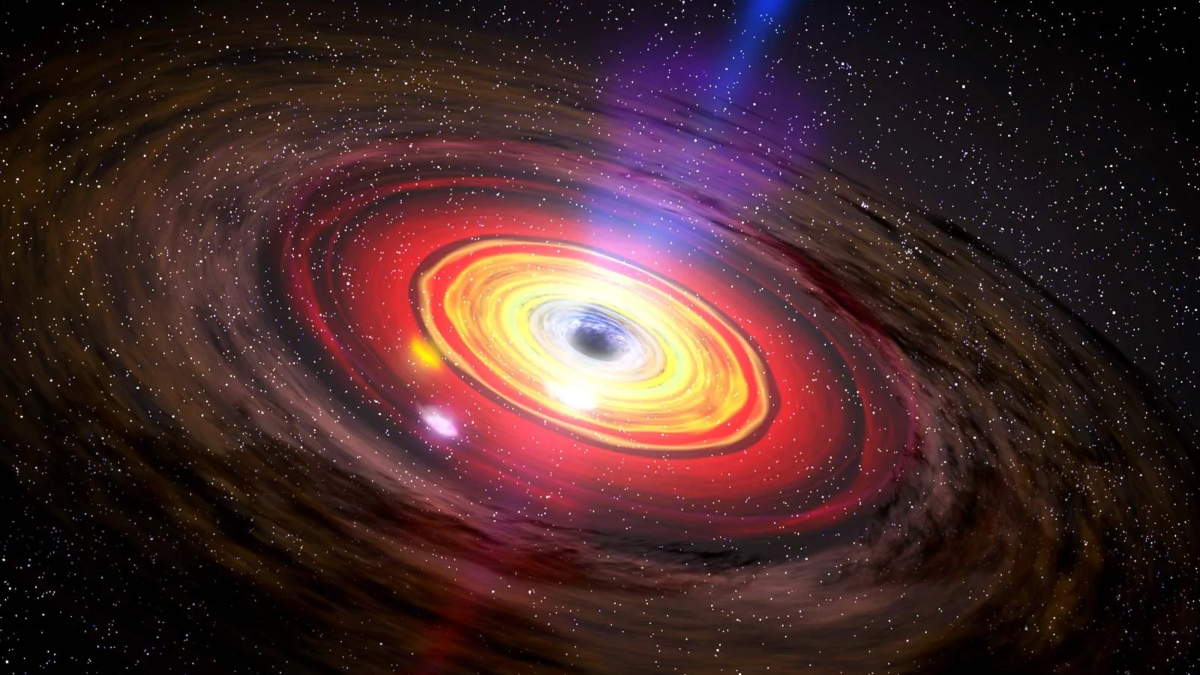

Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity has once again been validated as astronomers observed a previously elusive area at the edge of black holes, where matter can no longer stay in orbit and instead falls inward. This region, known as the “plunging region,” was detected for the first time using telescopes capable of observing X-rays.

A team of astronomers studied a black hole located approximately 10,000 light-years from Earth in a system called MAXI J1820+070. The black hole, with a mass estimated at seven to eight times that of the sun, was observed using NASA’s NuSTAR and NICER telescopes. These observations allowed scientists to understand how hot gas from a nearby star is sucked into the black hole.

“We’ve been ignoring this region, because we didn’t have the data,” said Andrew Mummery, the lead author of the study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. “But now that we do, we couldn’t explain it any other way.”

The plunging region is likened to the edge of a waterfall, where material loses stability and crashes inward, unlike the stable orbiting material which resembles a river. “Most of what you can see is the river, but there’s this tiny region at the very end, which is basically what we found,” Mummery explained.

While the event horizon is closer to the center of the black hole and prevents anything from escaping, light can still escape from the plunging region, although matter is inevitably drawn in by the intense gravitational pull.

This breakthrough in observing the plunging region could significantly enhance the understanding of black hole formation and evolution. “We can really learn about them by studying this region, because it’s right at the edge, so it gives us the most information,” Mummery noted.

Despite the lack of an actual image of this black hole due to its distance and size, future projects aim to create the first movie of a black hole. The Africa Millimetre Telescope in Namibia, expected to be operational within a decade, will join the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, which captured the first image of a black hole in 2019.

Christopher Reynolds, a professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, emphasized the importance of this discovery in refining models of matter behavior around black holes. “It can be used to measure the rotation rate of the black hole,” Reynolds said.

Dan Wilkins of Stanford University called the development exciting, highlighting that previous hypotheses about the plunging region can now be tested with new data. “This will be prime discovery space over the next decade or so,” Wilkins said, referring to upcoming advancements in X-ray telescope technology.